The End of Sex, Death, & Humanity

BEWARE SPOILERS

We go into every post assuming you’ve already watched the films being discussed.

Ghost in the Shell is freely available on the Roku Channel as of this writing (4/26/22), but we don’t recommend it. See, they’re showing the English dubbed version, and even though we don’t have strong opinions on the whole dubs vs subs thing that anime fans go on about, in this case, the dubs are bad. Everyone sounds loud and bubbly, which very much goes against what’s happening onscreen.

Our advice, watch a subtitled version, if you can find one. Unfortunately, we couldn’t find a freely available subtitled version on any of the bigwig streaming services. So… we’re not saying you should search for it elsewhere, but we have faith that you could. If you wanted to. But we’re not suggesting anything.

You may have noticed that we’ve been a little slow with our articles lately. There are a lot of reasons for that, including a death in the family and two very frightening instances of car trouble, but aside from life continuing to pummel us into the ground, we’ve also been working on exciting stuff that’s not a bummer to talk about.

Very soon, we’ll be launching an online store with merch featuring custom Other Folk artwork! The hope is that profits there, along with those from our Patreon Supporters, will get us to where we can pay our contributors.

Right now, though, we’re continuing with our Dissection series on animated horror, which Eric launched with his post on Netflix’s claymation horror film, The House, tracing the story of environmental horror brought on by human greed, materialism, and self-delusion regarding all the doom we’ve created. Real sunny stuff!

Today, we’re looking at Mamoru Oshii’s iconic 1995 anime, Ghost in the Shell. Often credited as popularizing anime in the Western World, this film, based on Masamune Shirow’s manga of the same name, has gone on since its original release to spawn countless sequels, spin-offs, TV shows, video games, and manga. It’s inspired media franchises like The Matrix (via Business Insider), and—according to folks like The L.A. Times’ Charles Solomon and Vulture’s Emily Yoshida—is largely considered one of the most important films in anime history.

It’s also an incredibly disturbing work of science fiction that explores existential dread through unflinching body horror, as well as philosophical horror about the demise of humanity following the technological singularity. The singularity, as we’re sure you know, is an idea that’s circulated among scientists, philosophers, and science fiction writers for many decades now. (If you don’t know, or you aren’t actually familiar with the term, the book Singularity Hypotheses: A Scientific and Philosophical Assessment, while a hefty read, is a thoughtful and easy-to-understand exploration of it all.)

But the basic idea of the singularity boils down to the suggestion that, some time in the not-so-distant future, technological development will begin to accelerate so rapidly that we can neither control nor reverse it. How that happens and what the results could be tend to vary depending on who you ask, but most versions of the hypotheses come back to either the evolution of artificial intelligence or the merging of technology into human bodies.

In Ghost in the Shell, humanity enters the event horizon from two different directions. The film follows one of the beings who’s crossed this threshold, Major Motoko Kusanagi (Atsuko Tanaka), as she follows the gravitational pull of the Puppet Master (Iemasa Kayumi). Kusanagi, her partners Batô (Akio Ôtsuka) and Togusa (Kōichi Yamadera), along with every other member of Section 9, thanks to advanced cybernetics, is effectively immortal so long as the "ghosts" (souls) encased in their cyberbrains remain alive. As the film goes on, a bleak and meaningless future comes into view—one devoid of sex and death, in which our humanity is reduced to little more than a whispering ghost. At the film’s climax, Kusanagi and the Puppet Master converge in one singularity, signaling the slow end of humanity—well, unless you count all the sequels and spin-offs, in which humanity still exists, but shush; the movie’s better this way. It’s more horrifying.

The Shell of Theseus

Plenty of thinkers have thunk on the singularity over the years—including Henry Adams, writer, historian, great-grandson of U.S. President John Adams, and grandson of President John Quincy Adams. According to Acceleration Watch’s John Smart, Adams, who he credits as “Earth’s First Singularity Theorist,” began speculating on these singularitarian ideas in the 1904 essay, “The Law of Acceleration,” and the 1909 essay, “A Rule of Phase Applied to History.” In his work, Adams suggested that accelerating progress will lead to a drastic shift in human existence. He even detailed the stages humanity would go through before reaching a phase change that involved humanity’s relationship with technology, believing the most pivotal change would occur no later than 2025. One-hundred years later, as Smart notes, mathematician and science fiction writer Vernor Vinge renamed Adams’ “phase change” to the more science-y and specific “technological singularity.”

In sum, scientifically-minded folks have been discussing the possibility that accelerating progress in disruptive technologies like artificial intelligence will lead to an event that sparks radical change to the very nature of humanity for a long time. Not only that, but an awful lot of them (not just Adams) have suggested that an event—the “event horizon”—somewhere between right friggin’ now and 2050 will trigger an inescapable spiral into this pivotal and unpredictable moment of existential change of our species.

Vinge chose the word "singularity" as a metaphor. Within the center of a black hole—its gravitational singularity—quantities that are otherwise meaningful, like density and speed, become infinite and therefore meaningless. Before that point, though, comes the event horizon, the threshold surrounding a black hole beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape its pull. Because light can’t escape it, you can’t see the threshold until you’ve crossed it.

You can probably already see how this is an apt metaphor. Most thinkers on the technological singularity say we will eventually cross a threshold in our technological development that we won't be able to see until we’ve entered it, after which the rise of Skynet will become inevitable. Then, Arnold Schwartzennager will turn us all into batteries and put us inside the Matrix, where we’ll race on flashy red and blue digital motorcycles over a giant circuit board. We’ll never die, and all the things we think make us human—love, anger, fear, compassion, jealousy, kindness—will become meaningless.

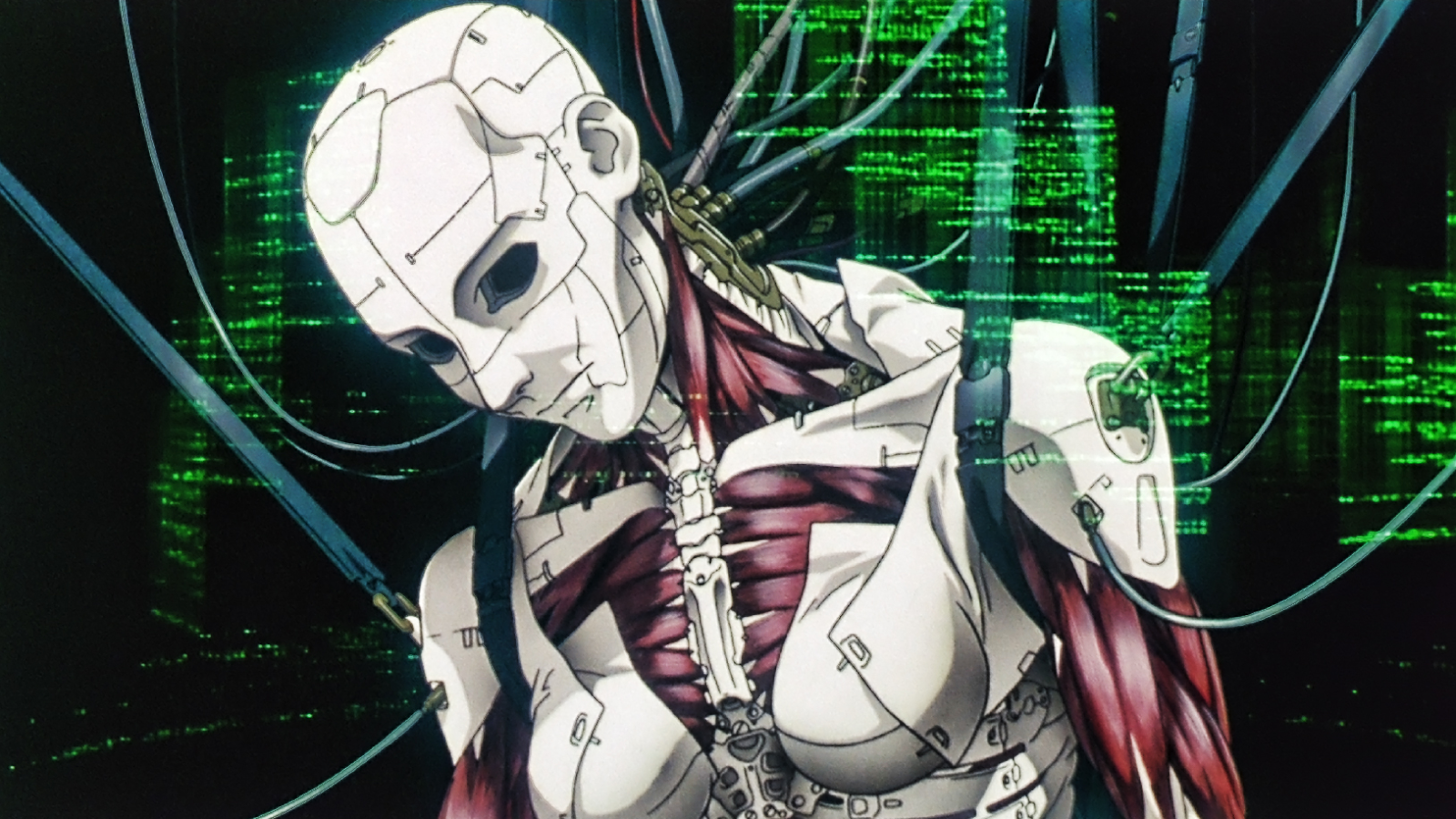

Ghost in the Shell picks up just as Kusanagi and the Puppet Master cross the event horizon at different points, pulling the rest of the world in with them—notably, in 2029, just four years after Adams foretold, and only a couple decades before more recent prophecies around 2045 from scientists, philosophers, and science fiction writers. In the Puppet Master, Oshii’s film depicts a common event horizon prediction, in which a self-improving, autonomous lifeform is born from the primordial sea of information.

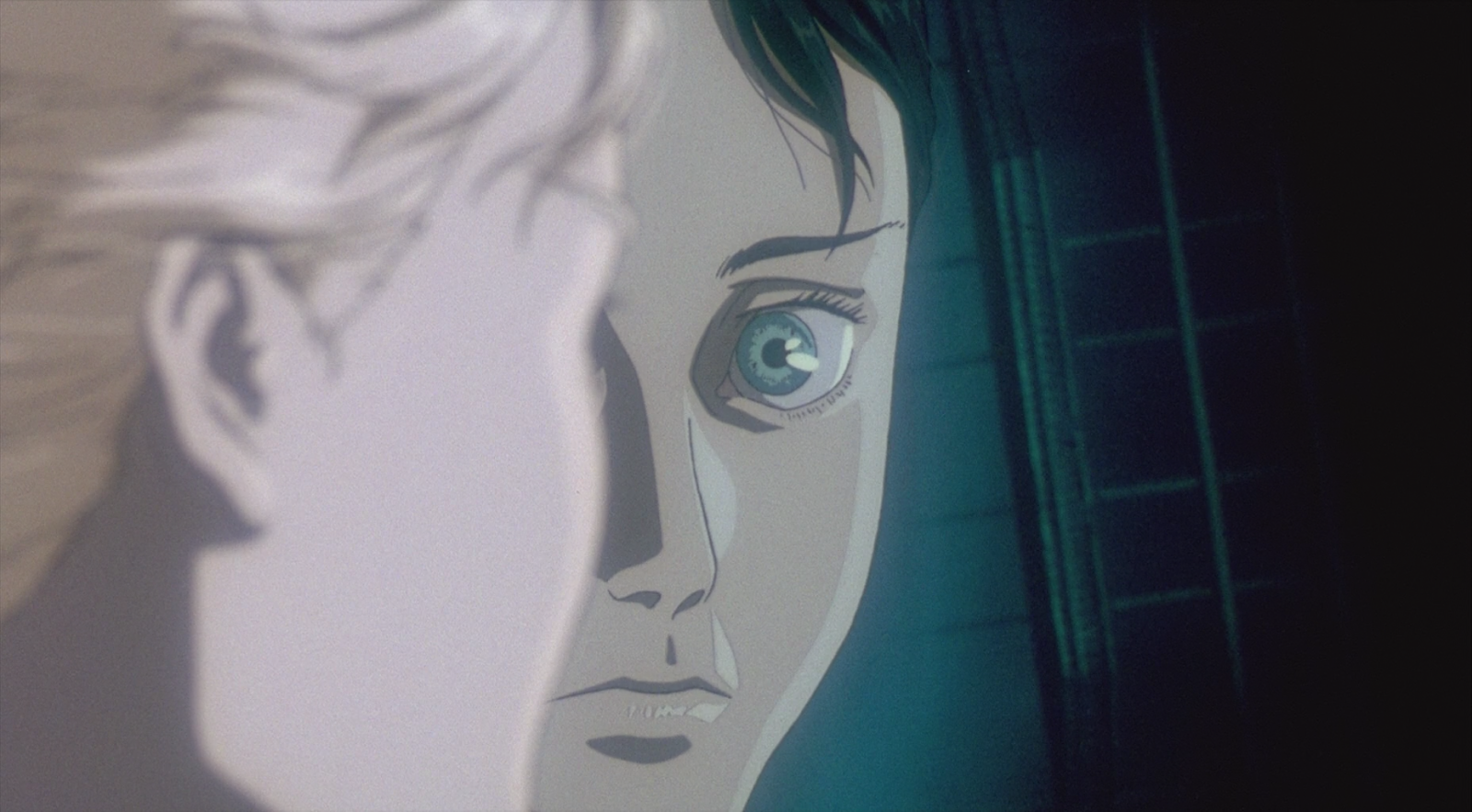

Kusanagi represents a second oft-imagined event horizon scenario in which humans replace part after part of their biological bodies with machinery. Eventually we Ship of Theseus ourselves into a whole other species. In Ghost in the Shell, Kusanagi’s body has been fully replaced with a mechanical shell. All that’s left of her humanity is the soft whisper of her vanishing ghost. When she learns of the Puppet Master, she wonders aloud, if technology can give birth to a ghost, then how can she trust that her ghost—her soul—is that of her original, human self? She wonders too, did that original human ever exist at all?

In a world where humans can replace every part of the body with cybernetics, preserve consciousness across bodies, and rewrite memories, these questions become unavoidable. To cope with the philosophical horror, Kusanagi seeks out feelings of “fear. Anxiety. Loneliness. Darkness. And, perhaps, even hope.” In an effort to know these feelings, she dives alone at night, in a body that, with a single malfunction, could sink and send her to a watery death. She does this because the reminder and risk of death allows her to feel vulnerable and human again.

For her cybernetic body she’s paid the cost of everything else that makes us human—makes us feel alive. Her sexuality has been erased. She’s lost her fear of death entirely. She seems to take no pleasure in life, nor to feel any kind of physical pain. Only alone in the dark and consuming depths of the water does she feel anything of her humanity.

The Puppet Master, on the other hand, feels no such fear, anxiety, loneliness, darkness, or hope. Instead, he's driven to attain those two most essential realities of human existence: procreation and death. To be able to give birth to unique beings, not copies, and to be able to experience mortal death, he believes, will make him truly alive. For him, unlike Kusanagi, humanity is of little concern. But to become a true lifeform is akin to spiritual transcendence.

The Beginning: Sex & Procreation

Major Kusanagi leads a unit called Section 9 (akin to secret police) that specializes in cyber-based crime. She and her colleagues are tasked with tracking down a terrorist going after world leaders and hacking into their and other human brains. When we meet Kusanagi in the opening sequence, we learn right away that she loves naked combat.

Why naked? Don’t know. Other people do the optical camouflage thing with clothes on, but not Kusanagi. She’s totally and unabashedly nude, right down to her lack of a vagina. (Sure, she makes a comment in the opening scene, blaming the noise in her head on her period, but that’s just a quippy joke, because she doesn’t have any reproductive organs. Her body’s almost all cyborg, after all.)

Notably, her nudity isn’t sexualized (as we’ve come to expect with an awful lot of anime). There are no leery looks or suggestive comments related to her decision to perform her duties naked (or with her skintight suit). She doesn’t flout her nakedness, but she also doesn’t cover it up, because she’s not ashamed of her Barbie doll anatomy. It just… is.

In fact, Kusanagi’s nudity is so desexualized as to feel inhuman. While her partner Batô experiences some discomfort with his colleague's choices—perhaps a remnant of his own fading humanity—and averts his gaze or drapes a coat over her, Kusanagi embodies a coming phase of human evolution that’s devoid of even the consideration of sex.

Throughout the movie, her dehumanized nudity feels unsettling, and her eventual merging with the Puppet Master marks an alien form of procreation. Combine all this with various conversations about how our memories are simply processes that inform us of who we are, and that all brains are essentially computational machines, and sex and romance quickly become meaningless.

The union of Kusanagi and the Puppet Master is not sexual or romantic, but rather religious and transcendent. They “slip our bonds and shift to the higher structure.” This is the beginning of a radical and irreversible phase change brought about by the deaths of the living being who became a bit of code inside a brain shell and the bit of code who became a living being. Their deaths and rebirth as a new and separate lifeform (now in the creepy body of a “little girl”) mark the inevitable end of humanity as we know it.

The End: Attaining Death

Kusanagi is, in essence, yet another model of herself living on after the previous version of herself died. She and most of Section 9 are cybernetic beings who must trust that the operators who designed their new bodies kept their ghosts intact. It’s this fact that has Kusanagi wondering who she really is—and whether her ghost is entirely fabricated, or if it’s a distant copy of a copy of the person she once was.

In her discussions with Togusa and Batô, she speculates on meaning and the idea of the self: if all your parts are replaced, do you at some point cease to exist? Are you still you?

The answer, Ghost in the Shell tells us—at least to that latter question—is no. You might be another version of the original you, if that original ever existed, but that’s debatable. Still, the question remains whether that version of you would feel and experience life the same way as the original you did, if ever there was one. And, if you have access to all of those original memories, wouldn’t you at least feel that you were the true version of yourself? As if all those past selves were in the process of becoming you?

But then, what if those original memories are locked away, somewhere deep inside, and you only have the uncertain memories of what once was? Toward the end of the film’s first minor story arc, we discover that all this ghost-hacking stuff has implanted memories of a wife and child into a man who was never married and never had a child. He learns of their non-existence during an interrogation after he’s arrested for aiding the terrorist the authorities have started to call the Puppet Master.

The officers tell him his ghost has been hacked. They say his family, the divorce, the affair he remembers, “They’re all fake memories. Like a dream.” He learns that his apartment is essentially an empty bachelor pad, and that the picture he tried to show a colleague, of him and his daughter, is just one of him. The camera lingers on the man’s face as tears roll from his wide, red-rimmed, motionless eyes. Clearly in shock, he mumbles, “How can I erase those fake memories.” It’s all but impossible.

In other words, he’ll be forced to live with the memory of his non-existent family, suffering the intimate loss of two people who were very real to him even though they weren’t actually real. He has no one to mourn with, no one who ever knew them, and to speak of them publicly is to be reminded that they were never born, never died, never existed.

The man, who says “My daughter’s my life,” is left to wonder: Without her, what is his life? Who is he? Those sorts of questions must be especially terrible for a parent who’s lost a child. Here, though, the memory itself is false, so not only has his family died, but that version of himself who had a wife and child has died too. In this sense, everything he understands about his world becomes meaningless, and therefore, his life, too, becomes meaningless.

But the film’s question of identity isn’t about whether who’s left of the garbage man is the same person as the fabricated father or the lonesome bachelor who came before that. In that same vein, ultimately, the question of whether Kusanagi has been Ship of Theseused into oblivion is interesting, but it’s also purely academic and not the movie’s real concern. Instead, the most pertinent questions for Kusanagi and the Puppet Master are: Who are they now, and who will they become after the first full convergence of human and machine eliminates their current senses of self?

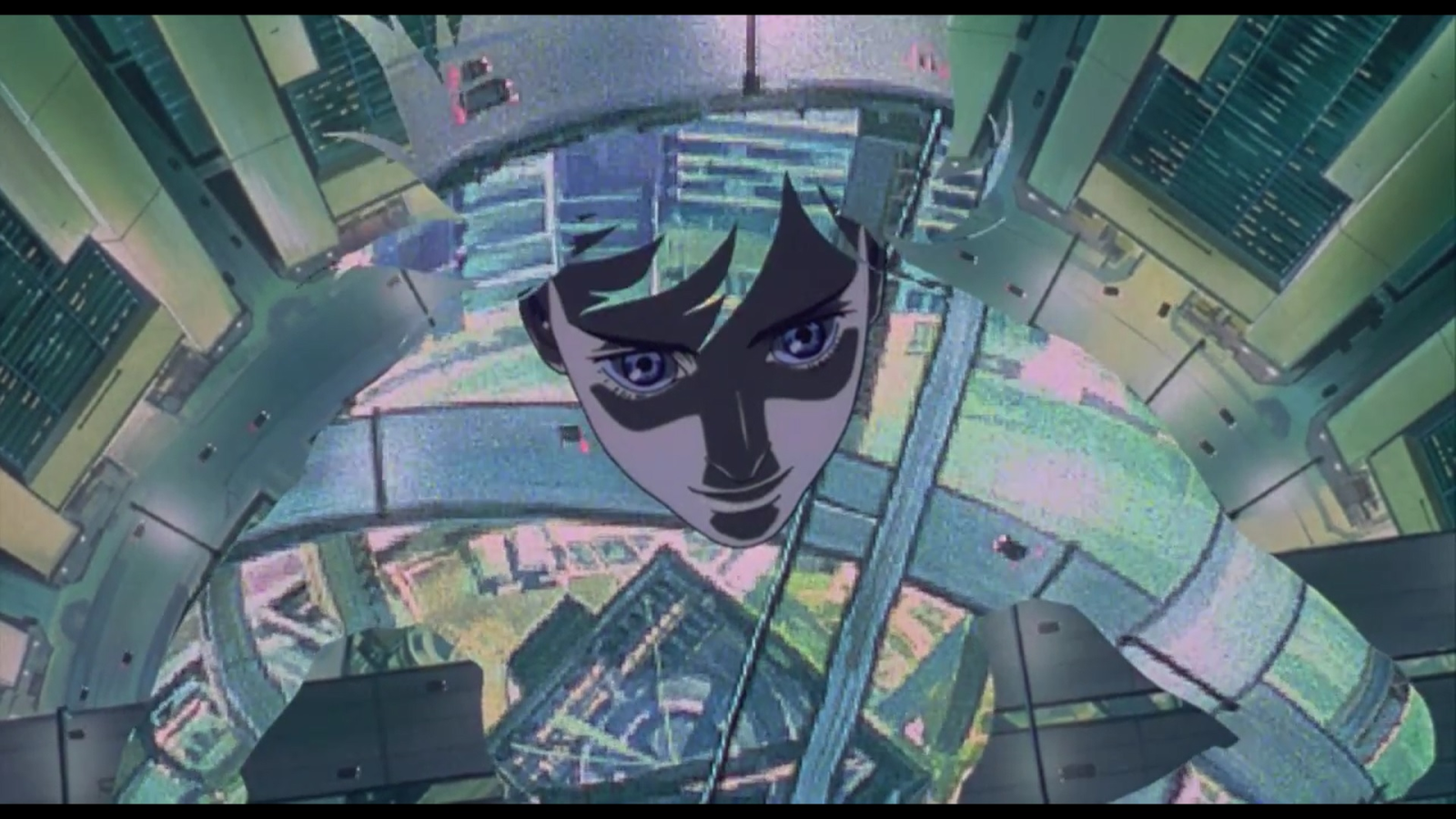

For Kusanagi, the idea of being consistently upgraded—“overspecializing,” as she puts it during a conversation with Batô—leads to a “slow death.” Her fatalism, in conflict with the sense of immortality brought on by her cybernetic body, leads her to take extreme risks with that body, seeking out experiences that remind her of death—memento mori, as it were. She even takes on a tank by herself, on foot. In one of the film’s most memorable moments of body horror, she rips her own arms while trying to pull the door off of said tank.

After that, a clamp on the tank grabs her by the head and begins to crush it. Does Kusanagi scream? Does she react at all with signs of pain or emotion? Nope. In this world, death means nothing because it can be so easily undone, so Kusanagi seeks a death that can’t be undone: the death of her brain and, with it, her ghost.

Kusanagi’s morbid reasons for diving despite Batô’s protests, her constant need for repair after reckless use of her cyborg body, and finally, her consent to converge with the Puppet Master all stem from her ghost’s death wish.

Like her, the Puppet Master has also come to seek death, viewing the experience as an inseparable part of life. Whereas Kusanagi has reached this point through the living of countless unremembered selves, the Puppet Master has come to aspire to “attain death” as part of his goal to become a living being.

The Middle: I Think. Therefore, Nothing.

Ghost in the Shell explores existential questions of selfhood, the slow vanishing of humanity, and the idea that we will, eventually, become unfeeling machines—desensitized, unempathetic vehicles of progress and self-preservation. Our characters—particularly the emotionless Kusanagi—are often callous, nonchalant, and uncaring.

Atsuko Tanaka’s voicing of Kusanagi, like Iemasa Kayumi as the Puppet Master and much of Akio Ôtsuka’s performance as Batô, is purposefully flat, because these characters are unfazed by chaos, violence, sexuality, humor, and tragedy. Kusanagi and other members of Section 9 show no hesitation whatsoever to fire their weapons in large crowds of people. After watching the interrogation with the garbage man who lost his nonexistent family and the self he thought he was, Kusanagi and Batô are intellectually curious but emotionally unmoved. Their conversations sound at times like two machines comparing notes on topics of existential and epistemological philosophy—that is, questions of existence and of how we know what we know.

Even before the film’s events, humanity in Ghost in the Shell’s world is already in the midst of a drastic phase change. There is no stopping the Puppet Master’s emergence, born as he is from our own networks of information, and there is no stopping his and Kusanagi’s eventual convergence.

Through disturbing body horror, existential and epistemological dread, and the reduction of humanity to a whisper—the film gives us answers: in the absence of procreation and final death, life loses its significance. If there is no beginning and no end to it, then there is no middle, and the right now of existence is disconnected from all that gives it meaning.

The Puppet Master claims that life is just nodes of information out of which a ghost, a soul, emerges. He seeks Kusanagi out because she has become so far-detached from her own humanity that all she has left of her human body is her brain, and she’s begun to question whether even that exists.

The philosophies of René Descartes are no help here. “To think,” in this world, confirms nothing of whether, “therefore, I am” my original self, or a copy, or a copy of a copy of a copy. To simply know that you exist is not sufficient if your definition of self depends on your memories, which you can’t trust, and your humanity, which has been reduced to a distant echo.

This is the slow demise of humanity Ghost in the Shell predicts, and it follows into the film’s direct sequel, 2004’s Innocence. By this point, just a few years later, much of humanity has gone the way of the cyborg, having become so machinated that even the emotionally blunted members of Section 9 comment on the flat reactions other characters have to everyday conversation, not to mention scenes of terrible violence and depravity.

Thus the slow demise of humanity comes, not with a bang, but with a meaningless whimper, buried deep under a shell of plastic, metal, and silicon.