Cartoon Bunnies & The Incomprehensible Power of Humanity

Beware Spoilers

We go into these articles assuming you’ve already seen or read whatever we’re talking about. We don’t hesitate to spoil anything.

In this particular article, we talk about both the film and the novel Watership Down. There’s a good chance a lot of you have seen or read one and not the other. The movie is pretty faithful to the book, so if you’ve seen it, there’s not a whole lot to spoil in the book. And if you’ve read the book, there’s nothing to spoil in the film.

We know… This article’s been a long time coming, and that’s putting it very mildly. It’s been slow-going for a bunch of reasons—not the least of which are personal and financial, but we won’t get into that here. The bigger issue is that Watership Down ranks very high on our list of favorite animated films and on Eric’s list of favorite novels. See, when we write about things we love, we want to write everything about them, but then the actual writing becomes very overwhelming, making it hard to type anything coherent because we keep shooting off in different directions.

If you read the Judgment we posted a couple weeks ago, you’ve already seen one of the directions Eric started heading before realizing it wasn’t going to work for a longer article. That’s because the questions of whether Watership is appropriate for kids and whether it qualifies as a horror movie, while interesting, have been covered again and again in popular media. We just didn’t have much to add to that conversation beyond Eric’s personal relationship with horror when he was a kid, and that wasn’t going to net us enough words for a good Dissection.

So we’re trying again. This time, we’re looking at the role and influence of humanity in the film and novel as an incomprehensible and corrupting force of cosmic horror. We maim and destroy for convenience, and as a result, we drive other animals to behave in strange and terrible ways. Cowslip and the other rabbits of the Snare Warren make an unspoken bargain with the humans who keep them safe from predators, disease, and hunger, in exchange for their passive acceptance at being snared and harvested for their pelts and meat; and General Woundwort, after surviving the gruesome deaths of his entire family at the hands of a farmer, becomes so traumatized he establishes a militarized, dystopian warren with himself as dictator.

In short, Richard Adams’ novel and, to a slightly lesser extent, Martin Rosen and John Hubley’s 1978 film adaptation, depict humans as selfish and disinterested gods who disfigure environments and ecologies, bringing death, destruction, and madness to the rest of the world for the sake of a few pelts, a cabbage patch, an apartment complex.

Humanity’s guilty of far worse environmental destruction than Richard Adams explores in his strange and at times disturbing masterpiece of a children's book. He wrote it in a time before the Exxon-Valdez and BP oil spills of 1989 and 2010 respectively; before the nuclear meltdowns in Three-Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima; and before terms like “climate change,” “ocean acidification,” and “sea-level rise” had even entered most of our minds.

By contrast, Watership Down’s environmentalism can seem quaint in 2022, with its focus on rural farmers and residential construction. But viewed on a smaller scale—specifically, the scale of a rabbit’s local habitat—Watership, especially the book, becomes a broad and elemental criticism of humanity’s role in the world.

To other creatures, we’re utterly incomprehensible, godlike destroyers. We suck smoke from burning white sticks, we ride upon great mechanical beasts known to rabbits as “hrududus” (presumably for the sound of an engine), we kill in far greater numbers than the “elil” (rabbit predators), and we transform the very world itself. What’s more, we do so not for food or territory or revenge or hatred, but out of simple convenience and disregard for the creatures in our way. Like the twisted but all-powerful gods of HP Lovecraft, when the rabbits of Watership are unfortunate enough to have close contact with us, they’re nearly all killed or driven to madness.

The Cult of the Silver Wire

Our first clear encounter with rabbits whose interactions with humanity’s godlike power have left them dead or mad comes with the rabbits of the Snare Warren.

At the beginning of the story, a young rabbit named Fiver, who seems to have supernatural premonitions, sees a field flooded with blood and becomes convinced death is coming to their warren, Sandleford. The Chief Rabbit dismisses his warnings, so Fiver and a small group, led by his older brother Hazel, set out on their own to find a new home.

After a treacherous journey, the group discovers a warren thin in numbers and looking for new rabbits to join. A rabbit named Cowslip, who holds the authority of Chief Rabbit but rejects the title, invites the group into the warren, offering shelter and food, which Cowslip and company have stockpiled from scraps the farmer throws away.

At this point in the book, Fiver insists, “it’s simply that I know there’s something unnatural and evil twisted all round this place. I don’t know what it is, so no wonder I can’t talk about it. … I’m close to this—whatever it is—but I can’t grip it. If I sit here alone I may reach it yet.”

In the roof of their main hall, he sees not tree roots, but bones, holding up the earth around the home of these strange rabbits who have no fear of predators, who perform odd greeting rituals, and who make shapes by pressing stones into the dirt walls of the warren. They don’t answer when the group asks why so many of the tunnels are empty or why the man leaves abundant supplies of unpoisoned food. They are, in every way imaginable to Fiver, Hazel, and the rest, very unnatural rabbits.

What’s more, in the film, these “unnatural rabbits” surprise our group by rejecting cunning stories and legends about El-ahrairah, Prince of Rabbits. In the novel, they don’t necessarily object to these stories, but they don’t take them seriously either, dismissing them as old-fashioned, folksy amusements: “I always think these traditional stories retain a lot of charm,” one of them says of a story told by Dandelion, the bard of the group. The rabbit adds, “especially when they’re told in the real, old-fashioned spirit.”

These rabbits prefer high-minded, lyric performances, like those of their own Silverweed, who recites a poem about the wind, a stream, and “the autumn leaves.” He describes them as guides to the land of the dead, closing each of the first three verses with a variation of:

I will go with you, I will be rabbit-of-the-leaves,

In the deep places of the earth, the earth and the rabbit.

The poem ends with an even more explicit verse about culty death worship:

O take me with you, dropping behind the woods,

Far away, to the heart of light, the silence.

For I am ready to give you my breath, my life,

The shining circle of the sun, the sun and the rabbit.

As it turns out, these rabbits have accepted an unspoken bargain with the man who owns the farm they call home. Some years ago, he had begun to rid the land of predators and to keep the rabbits well-fed. “And then,” writes Adams, “he snared them—not too many: as many as he wanted and not as many as would frighten them all away or destroy the warren.” As for the effect of the farmer’s plan on the rabbits, “They knew well enough what was happening,” Fiver tells them, having finally come to understand his morbid visions of the warren, but they “pretended that all was well. … They forgot the ways of wild rabbits” and taught themselves

marvelous arts to take the place of tricks and old stories. They danced in ceremonious greeting. They sang songs like the birds and made Shapes on the walls; and [told] themselves that they were splendid fellows, the very flower of Rabbitry, cleverer than magpies. They had no Chief Rabbit—no, how could they? ... [H]ere there was no death but one, and what Chief Rabbit could have an answer to that?

The Snare Warren rabbits, like the Lotus Eaters of Homer’s Odyssey, lure travelers into their vast warren, offering food and safety from natural predators. They indulge frivolous wit and entertainment to distract from the truth: the rabbits have built a death cult within their home of silver wires, sacrificing themselves and one another in worshipful resignation to the wire and to the farmer who protects them, until the day he harvests them for flesh and pelt.

The Gassing of Sandleford Warren

After they escape the bunny death cult, the group eventually finds a suitable place to build a new warren at Watership Down. Before they’ve fully settled in, though, the captain of the “Owsla” (rabbit-speak for guards or police) who had tried to stop them from leaving Sandleford Warren comes crawling after them, bloodied, beaten, and very near death, having narrowly escaped being gassed to death.

Here again, we get a glimpse of the incomprehensibility of humanity and the great terror and doom we spread across the natural world.

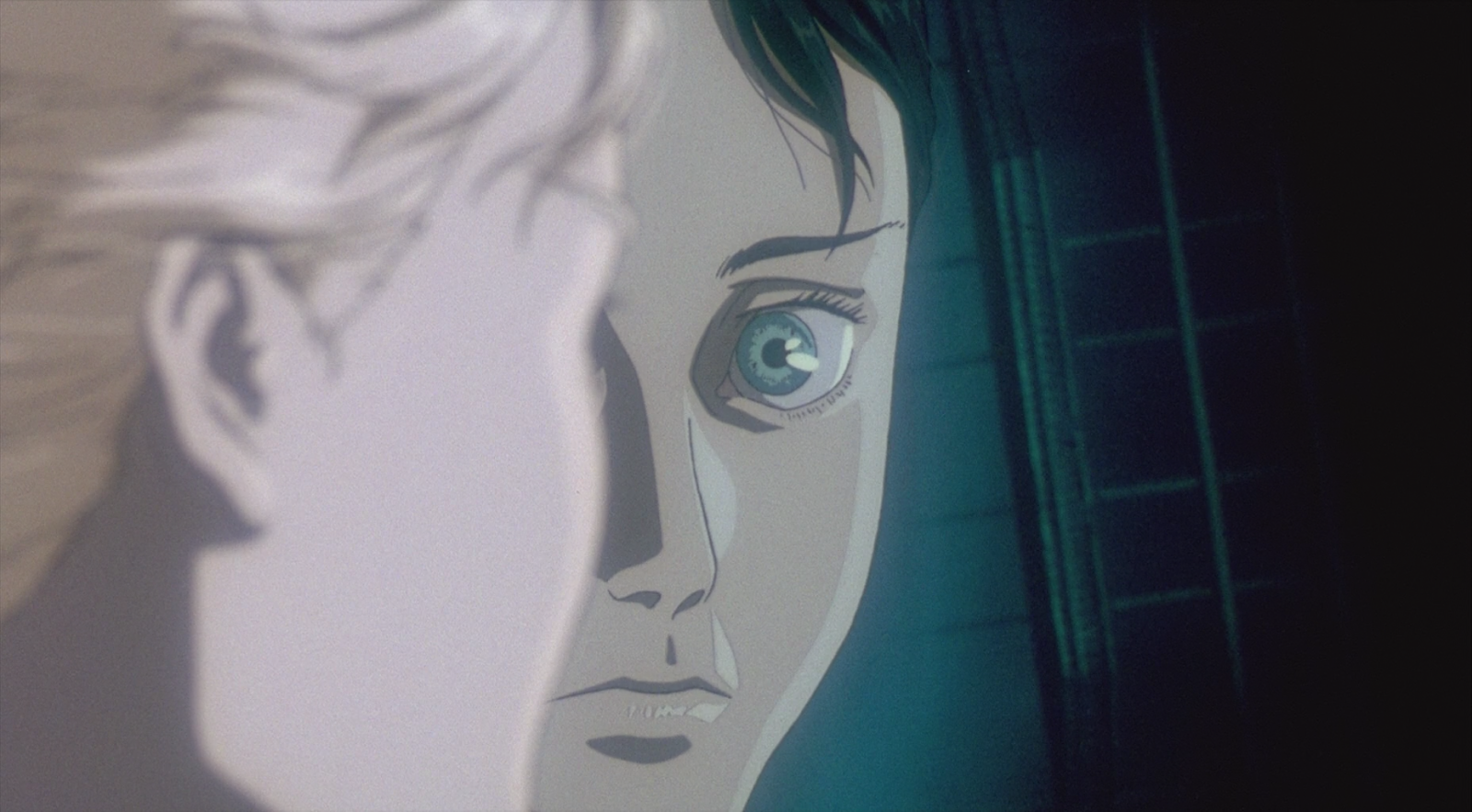

In the film, Holly’s the sole survivor, and his description of the fatal event is spooky, accompanied as it is by psychedelic images of ghostly rabbits trapped underground. But it's also toothless. With each sentence fragment, it stops short of being truly disturbing:

Men came. Filled in the burrows. Couldn’t get out. There was a strange sound. You see, the air turned bad. Runs blocked with dead bodies. I couldn’t get out. Everything turned mad. Warren, herbs, roots, grass… all pushed into the Earth.

This scene often gets cited as one of the movie’s more horrific moments, but compared to the novel’s depiction of what probably actually happens to rabbits being gassed underground—plus the layer of rational, human-like thought to make it extra distressing—the scene in the film comes across tame. The psychedelia, believe it or not, is a kid-friendly way of representing a scene that is, in the novel, far more gruesome.

Holly tells the others he saw men fetching “long, thin, bending things … like lengths of very thick bramble. … There was a kind of hissing noise and—and—well, I know you must find this difficult to understand, but the air began to turn bad.” He can’t quite make sense of it all—these strange “bramble things,” the hissing, the gas. His description makes it sound like some terrible magic, an inconceivable power on the scale of godliness that can change the very air they breathe.

In fact, Holly escaped the worst of it, being near an exit when the gas came. In the book, he’s not the sole survivor, and is accompanied by another rabbit, Bluebell. The pair escaped with two others who died shortly after. Speaking of the rabbits who were trapped underground, Holly starts to say, “I can imagine what it must have been like—” but Bluebell interrupts, “You can’t,” and the few fragments Holly delivers in the film become four pages of Bluebell’s harrowing tale of rabbits “spluttering and gasping” from the gas, tearing each other to pieces as they try to escape. He goes on to recount what happened in a part of the warren called Slack Run:

There were all sorts of forgotten shafts and drops that led in from above, and down those were coming the most terrible sounds—cries for help, kittens squealing for their mothers, Owsla trying to give orders, rabbits cursing and fighting each other. Once a rabbit came tumbling down one of the shafts and his claws just scratched me, like a horse-chestnut bur falling in autumn. It was Celandine and he was dead. I had to tear at him before I could get over him—the place was so low and narrow—and then I went on. …

When Bluebell reaches the end of his story, Holly picks up from there, telling the group how they’d escaped with Pimpernel and Toadflax. Holly recalls Bluebell saying that humanity “hated us for raiding their crops and gardens.” But, in what would turn out to be his final words, Toadflax corrected him: “That wasn’t why they destroyed the warren. It was just because we were in their way. They killed us to suit themselves.”

This, from the perspective of Richard Adams’ rabbits, is the unfathomable terror of humanity. Not merely our godlike powers over the other species we share this earth with, but our use of those powers for purposes beyond the comprehension of any other creature. The hands of gods trap you in your own home, filling its exits with dirt. They use brambles to fill your home with “bad air.” Then they bring “a great hrududu” to turn it and everything around it inside out:

“Upon my life,” said Holly, trembling, “it buried itself in the ground and pushed great masses of earth in front of it until the field was destroyed. The whole place became like a cattle wade in winter and you could no longer tell where any part of the field had been, between the wood and the brook. Earth and roots and grass and bushes it pushed before it and—and other things as well, from underground.”

In Fiver’s premonition, the entire field was awash in blood. This and the dismembered bodies of rabbits and other creatures are the “other things” brought up “from underground.” Godlike, humanity has brought Fiver’s vision, which had once been too terrible to even imagine or accept, to incomprehensible reality, all “to suit themselves.” Because humans, like gods, work in mysterious (and often thoughtless) ways.

The Mad Dictator Bunny Rabbit

(Originally, this section was going to be called “The Mad Dictator,” but come on… How could we not?)

Overall, Rosen and Hubsley’s film is very faithful to Adams’ novel. They make few significant changes to the content—despite cutting a lot of pages for the sake of streamlining the story into a 102-minute children’s movie. It’s frankly impressive, given how long the book actually is. One regrettable cut, though, is Woundwort’s backstory, which brings us to our last example of humanity’s abysmal influence on the animal lives it touches.

By far, the largest part of both the film and the book is the conflict and aftermath with the authoritarian warren of Efrafa and its savage leader, General Woundwort. The mad dictator bunny rabbit has his Owsla rake their claws over every subject in Efrafa to signify the “Mark” they belong to. Each Mark has its own scheduled feeding time—the only time they’re allowed above ground. The Owsla, we’re told, have their pick of “any doe in the Mark …. The does are under orders and none of the bucks can stop you.”

On top of the state-sanctioned sexual assaults, the warren is grossly overcrowded, causing pregnancies to fail. At one point, we overhear Hyzenthlay, one of the main characters to emerge during the Efrafa chapters, as she delivers a poem, which ends:

The frost is falling, the frost falls into my body.

My nostrils, my ears are torpid under the frost.

The swift will come in the spring, crying “News! News!

Does, dig new holes and flow with milk for your litters.”

I shall not hear. The embryos return

Into my dulled body. Across my sleep

There runs a wire fence to imprison the wind.

I shall never feel the wind blowing again.

In short, Efrafa is an oppressive police state. But that’s not why our adventurers want to rescue the does.

After building out the new warren at Watership Down, they realize they have no does, and that means no litters, which means no future generations of rabbits. When Holly tells them of this awful place, the group resolves to infiltrate it, sending Bigwig to make contact and set things in motion to save those who wish to be saved from Woundwort’s tyrannical rule. (Also, let’s not forget, to get some does for mating season—which seems, shall we say, like a mixed ethical bag.)

“General Woundwort was a singular rabbit,” writes Adams. “Some three years before, he had been born—the strongest of a litter of five—in a burrow outside a cottage garden near Cole Henley.” Woundwort’s family took to raiding that garden on the regular, enraging the gardener:

After two or three weeks of spoiled lettuces and nibbled cabbage plants, the cottager had lain in wait and shot him as he came through the potato patch at dawn. The same morning the man set to work to dig out the doe and her growing litter. Woundwort’s mother escaped, racing across the kale field toward the downs, her kittens doing their best to follow her. None but Woundwort succeeded.

Soon after their escape, though, a weasel killed Woundwort’s mother “before his eyes. He made no attempt to run, but the weasel, its hunger satisfied, left him alone and made off through the bushes.” Woundwort was then picked up by “a kind old schoolmaster,” who brought him home and nursed him back to health.

But there would be no domesticating Woundwort: “In a month he was big and strong and had become savage. He nearly killed the schoolmaster’s cat” when it tried to torture him. Shortly after, Woundwort fled from his second home, found a warren, and took over, “snarling and clawing.” Far from fearing predators, Woundwort began to seek out fights with them, and when “he had explored the limits of his own strength, he set to work to satisfy his longing for more power in the only possible way—by increasing the power of the rabbits about him.”

Woundwort is driven mad by his experiences with humans, and thus, Efrafa is born, a fascist dictatorship led by a rabbit so traumatized by the death of his family that he becomes the most dangerous kind of leader: one boasting fearsome strength, all-consuming contempt for his enemies, and an obsession with protecting his and his allies’ power at any cost.

Terrible Gods Who Ravage the Earth

Near the end of the novel, Hazel, Holly, and Silver muse on the lessons of their adventures and the unnatural happenings within their own community. Holly comments on the unusual timing of “Three litters born in autumn … Frith didn’t mean rabbits to mate in the high summer.” Hazel explains that, for one of the does they rescued from a farmer’s hutch, “it may be natural for her to breed at any time, for all I know. But I’m sure that Hyzenthlay and Vilthuril started their litters in the high summer because they had no natural life in Efrafa.”

Silver chimes in that fighting in high summer is also unnatural—“fighting, the breeding—and all on account of Woundwort. If he wasn’t unnatural, who was?” Holly says the General “was a fighting animal—fierce as a rat or a dog. … He was brave, all right. But it wasn’t natural; and that’s why it was bound to finish him in the end.”

Like we said in the intro, Watership’s environmental message can feel quaint and overly simplistic: natural = good, unnatural = bad. But that quaintness and simplicity is an important part of what makes Watership so disturbing.

Nowadays, the notion of allowing things to be natural feels more like a marketing campaign than any kind of reality that we—as a species, not necessarily as individuals—are interested in creating. We’re more focused on how to use technology to dig us out of the messes we’ve created with our irresponsible use of past and current technologies. And those of us in power, for the most part, have little interest in saving the many, many species we’ve driven near extinction—not to mention the many, many more species we’ve driven to actual extinction.

The environmental message feels quaint because we’ve transformed the world to such an extent that leaving nature to its own processes would be grossly irresponsible. We’ve thrown countless ecosystems into chaos by introducing invasive species, by wiping out entire populations of predators, and by hunting in thoughtless and destructive ways. Many species who’ve survived in our wake have come to depend on our continued interference in their environments.

In that context, the idea of leaving nature to recover itself is heartbreakingly nostalgic for a time when doing so might have been possible. When Adams published Watership in 1972, we had already transformed the West with two Industrial Revolutions, and much of the rest of the world has caught up since then.

In 1972, we were, relative to the other creatures of the earth, gods. Fifty years later, in 2022, we’ve only increased in number, grown more powerful, and continued to transform the world as it suits us, heedless of the species who stand in our way. A “return to nature” is no longer possible—and it probably wasn’t then either. Now, as then, we have a choice: to continue on the path of destructive and selfish gods, as Adams’ novel depicts us, or to become benevolent deities, stewards who value the lives of the plants and other creatures around us.

It really is a wonderful kids’ movie.