Robots Make the Worst Ethics Teachers

Beware Spoilers

This week we’re bringing you another Dissection. As always, we go in assuming you’ve already seen the movie. If you haven’t seen Netflix’ I Am Mother (2019) yet, and if you don’t want us to spoil the hell out of it, go watch the movie now. We’ll be here, with all our spoilers, when you get back.

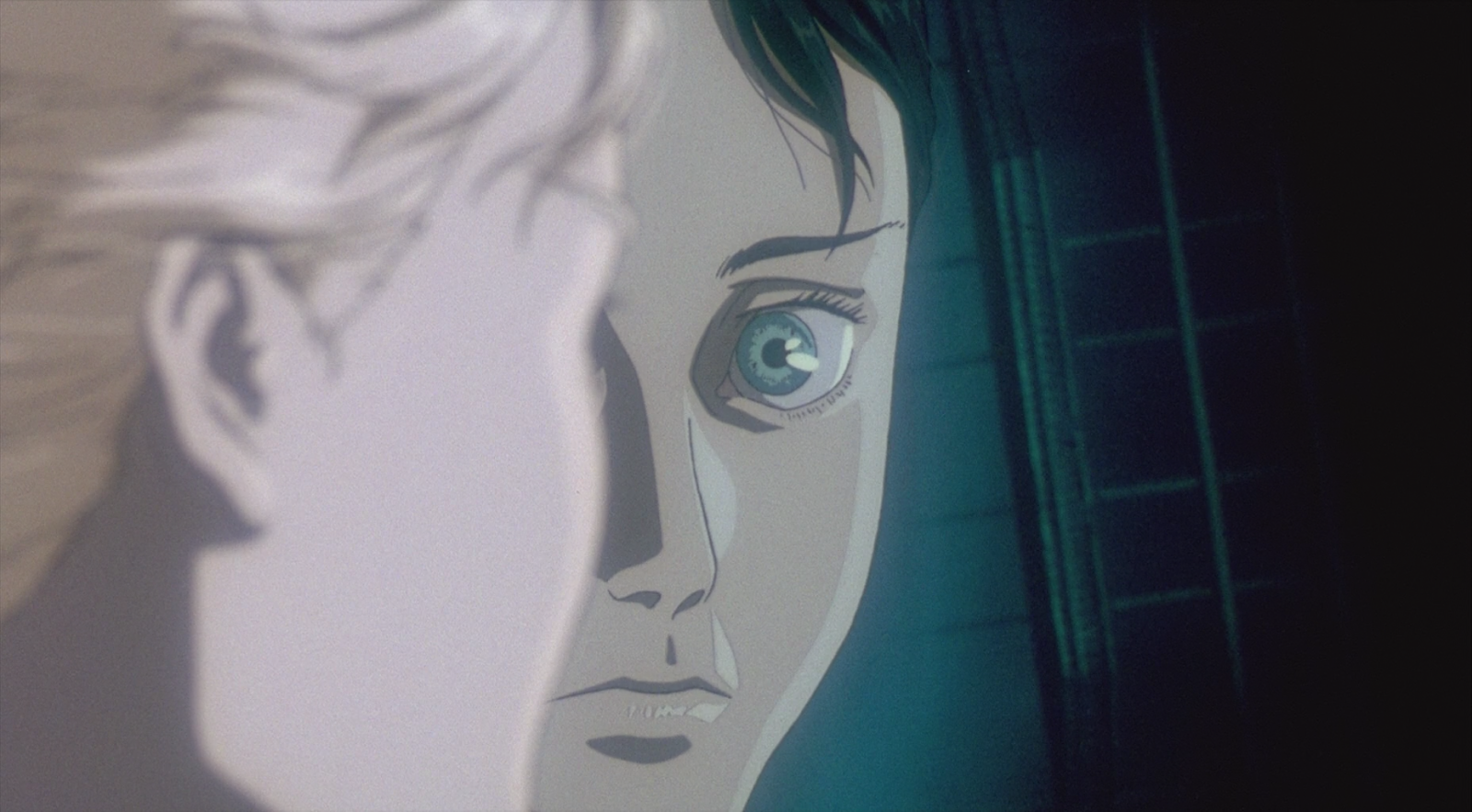

Grant Sputore’s 2019 Australian science fiction thriller I Am Mother is a visually rich depiction of a dystopian future. It's been praised for its engaging cinematography, a solid concept, carefully-crafted dialogue, and acute attention to detail—not to mention excellent performances from a very small cast.

At the same time, a few writers across the web have alternately accused or praised what they see as the film’s anti-abortion message. Most of those writers note the point and move on. A few, though, have spent quite a few words on the film’s ideas surrounding abortion. They rightly note its careful dialogue and pointed visuals that suggest an anti-abortion stance, but they wrongly take that as the stance of the filmmakers (or of their subconscious minds or of the film itself).

That’s not what’s going on here. Looking at I Am Mother as a clean-cut anti-abortion morality tale isn’t entirely wrong, but that interpretation misses some very important context about what the film is calling “abortion” and who, in the film, holds the anti-abortion stance. (Hint: it's the villain.)

The film talks a lot about the sanctity of life, but in a hypothetical sci-fi situation where the pregnant person’s been factored out of the moral calculus. And if pregnant people aren’t part of the calculus, then the calculus isn’t about abortion—not in the sense of aborting a pregnancy anyway. Morality, when it comes to abortion, revolves around 1) the rights of pregnant people and 2) the alleged rights of fetuses and embryos. If you cut the pregnant person out of the difficult and complicated question of whether it’s okay to end a pregnancy and stop the growth of a life, then you’re left with the much simpler question of whether it’s okay to stop the growth of a life when there's no cost to growing it (and when, in this case, the human race is almost extinct).

What I Am Mother Is Not About

While I Am Mother is not an anti-abortion screed, some, like Cosmopolitan’s Emily Tannenbaum—who’s outright dismissive of the film for that perceived message—take it that way. Others still, like Decider’s Anna Menta, say it has “an unclear moral message that may or may not be anti-abortion.”

We disagree. I Am Mother warns of a future in which unborn, potential lives are more valued than those of currently living people, in which those people have no freedom of choice or ultimate control over their own bodies. In fact, in this particular future, failure on a test about how much a little girl recognizes the "intrinsic value of human life" leads to her murder at the hands of an AI seeking to breed a morally perfect version of humanity because it was taught to value human life above all else.

In other words, Mother (chillingly voiced by Rose Byrn and body-acted by Luke Hawker) is the one who holds and enforces the anti-abortion stance, pursuing brutal and violent means to remake humanity into an ethically pure race. Daughter (Clara Rugaard-Larsen) wants to live and to see the births and lives of her “brothers and sisters”—who aren’t actually biologically related, by the way. And Woman (Hillary Swank) just wants to stay alive.

None of this strikes us as either pro- or anti-abortion. Maybe pro-choice though.

Robots Make the Worst Ethics Teachers

Professor Melissa Cain Travis of Houston Baptist University, in an essay published in the Christian Research Journal, calls the film an “artistic” exploration of a “pro-life theme.” In our research, she offers the deepest dive into the subject and makes the most forceful argument that I Am Mother is an anti-abortion film. So hers is the version of this argument that we’re going to dismantle.

Cain Travis acknowledges that we can’t really know if “the filmmakers intended this subtle yet discernible [anti-abortion] message,” but the fact that it’s there shows how we all have “subconscious intuitions” about “the humanity and intrinsic value of the unborn.” But also, she's pretty sure the creators meant to make an anti-abortion screed, since so much of the film seems, in her view, to be overtly about abortion and the sanctity of life. She’s kind of right, but not really in a good way.

She points to the facility’s depictions of embryos arrayed in racks that look like spinal columns: “The realism is incredible and intricate details are visible—perfectly formed little limbs with hands and feet, the outline of the spinal column, the silhouette of the brain, and the miniature face with developing eyes.” She concludes, “the humanity of the embryo is unmistakable.” Mother’s dialogue reinforces this idea. She calls them brothers and sisters and talks about them frequently in the future tense: “They’re small now, but one day they’ll be as big as you.”

To Cain Travis, this dialogue—which, let’s remember, comes from the film’s villain—“distinctly personifies the embryos and alludes to what philosophers call the substance view of human persons—the idea that a human being remains the same kind of thing from the moment he or she physically comes into existence.” The substance view says you remain the same kind of thing, in our case a human, throughout your “life, despite any changes in physical attributes such as size and level of development.” Whether you’re short or tall, have all your limbs or lost one in a terrible accident, grow your hair long or shave it off, you’re human. (Cain Travis says this is true from the moment a person “comes into existence” so she can sneak in the assumption that these philosophers are referring to conception, though this is far from clear cut.)

Then there’s the classroom scene, in which Mother—another reminder, the villain—is teaching Daughter about Kantian and Utilitarian ethics. She uses a variation of the classic trolley problem, which asks whether it’s ethically better to save several people by actively killing one person or to save one person but, as a result, passively allow several to die. Mother lays out the guiding Utilitarian principle: “a person is morally obligated to minimize pain to the greatest number possible.” Then she asks Daughter to choose which is the ethically right choice.

Daughter refuses to choose and instead argues that the problem is too complicated to be answered by this one principle without more context. Rather than more context, Mother retorts with another simple principle, from the philosopher Emmanuel Kant: “You don’t feel that every human has intrinsic value and an equal right to life and happiness?”

Cain Travis rightly notes that Mother means to include the columns of embryos when she says this, but then she half-wrongly says Mother has based her (unspoken) solution on the Utilitarian principle to minimize pain and maximize happiness by sacrificing for the greater good, rather than basing it on the Kantian principle of respecting every human life's intrinsic value and rights.

You'd have to hold some disturbing beliefs to conclude that the eugenicist, mass-murdering, self-aware AI is minimizing suffering. Specifically, you’d have to believe, as Mother does, in the most extreme, dogged, and inhuman versions of both Kantian and Utilitarian ethics.

Here’s what we mean: Mother works to minimize the suffering of future humanity by wiping out all of existing humanity for being morally corrupt. She then terraforms the planet she’s destroyed while killing all humans (except Daughter) to prepare the Earth for a more perfect humanity born of Daughter's 63,000 “brothers and sisters,” who will follow all of the ethical principles of morally corrupt humanity’s best philosophers, even when they contradict each other. She's breeding humans so ethically pure that they’re hypocrites.

Daughter calls out this hypocrisy early on in the film. When Mother’s grilling her on ethics and asks whether she believes in humanity’s intrinsic value and rights, Daughter quips, “I did last month, when you were teaching Kant.”

When Mother considers her medical version of the trolley problem, she doesn’t explicitly commit to any right choice of action, so technically, we can’t know her response.

Still, if we could wildly speculate for a moment, we have to wonder if maybe her solution involves collecting embryos from unwilling victims to be grown into a new humanity who’s immeasurably happier lives will balance out the quota of suffering imposed on the morally corrupt people she had to “abort.”

After all, Mother’s responsible for the near-extinction of life on Earth, except for Daughter and her 63,000 “brothers and sisters” housed in this facility. Even those embryos, though, only have “intrinsic value and equal rights” until they become a threat to humanity’s potential to be reborn as an ethically pure race. Because she values human life above all else, Mother must see humanity perfected, so she “aborts” living children who don’t meet her standards.

Again, this doesn’t sound very anti-abortion. It sounds like fixation on two conflicting principles like a machine caught in a feedback loop. The problem isn’t that she makes the ethically wrong choice out of two possibilities; it’s that she refuses to resolve those conflicts by considering nuance, context, human feeling, or the suffering of the people sacrificed for the supposed greater good.

What’s more, that Utilitarian principle of sacrificing for the good of others goes against another Kantian principle about not treating people merely as a means to an end. He says, if we recognize a person’s intrinsic value, we have to treat their interests as equal to the interests of all others, regardless of how many others there are.

In the end, our villain only values potential life and will sacrifice anyone and anything to protect it. In Mother’s psychopathic moral calculations, only the unborn are intrinsically valuable—because they are intrinsically innocent; everything else is either useful as a means to building a more perfect humanity or a threat to be killed and incinerated. (We don’t have to unpack more philosophers to explain why that makes her the villain here, right?)

What I Am Mother Is Actually About

For his part, director Grant Sputore has called I Am Mother “largely a study about what it means to be good,” and how artificial intelligence and sentient “robots will either save us from” our own self-destruction “or…expedite it” (according to The Verge).

We’ve explained before on this blog that a creator’s intended meaning, although it does matter, is not the end-all-be-all in what a piece of media actually means. Books and movies and shows and videogames have all kinds of meanings and ideas that their creators didn’t intend to put in them. That’s just how art works.

So, we’ll admit, there is an argument to be made that the film has an anti-abortion bent. Cain Travis isn’t wrong when she notes how much the embryos are humanized. She’s not wrong that the film uses language and imagery in ways that seem, intentionally or not, laced with anti-abortion sentiments and rhetorical devices. But, as we’ve already mentioned, most of that messaging comes from the movie’s villain.

Then again, there is one moment in the film that seems, at least at first, to support the anti-abortion interpretation better than others: among the clues Daughter finds that Mother has murdered children before her are the tablets they use to take their tests. When Daughter finds them and turns one of the devices over, we see the word “ABORTED” flashing dramatically in red.

On the one very heavy hand, this definitely looks anti-abortion; after all, the villain is aborting children! But remember, these children were all murdered after they were born and had lived for several years. No matter what the sci-fi doohickey says, that’s murder, not abortion.

Besides, just back away from what the creators meant or didn’t mean for a minute and think about the film itself. The reality of this world is that humanity has been nearly decimated, and human birth has been completely detached from sex, pregnancy, and the living human beings involved in making a kid. In that context, yeah, unborn embryos are sacred, because all the costs associated with sex, pregnancy, and birth have been removed and every potential life in this post-apocalyptic future exists on the brink of extinction. It’s hard to argue, in that context, against the importance of “birthing” those embryos.

At the start of the film, Mother is watching over 63,000 potential lives. When she chooses one from the columns, she places it in an artificial womb, where a fetus can grow into a baby in just twenty-four hours. All Mother has to do is wait.

The Easy Bake Oven approach to creating new life removes pregnant people—the people most directly affected by abortion issues—from the equation, making questions about abortion in the film basically meaningless. Remember, the “abortions” in the film are, in fact, murders of very unquestionably alive children, not embryos or fetuses.

If we go with directorial intent and take Sputore at his word, I Am Mother is about the relationships between humans, technology, and the complexities of practicing good ethics. A long-standing idea in science fiction is that artificially intelligent robots would struggle with human ethics, lacking the emotions necessary to understand them as more than a set of equations used to make moral decisions. Outraged by our inability to live according to our own moral standards, Mother decides that this version of humanity must be destroyed and replaced with a more ethical breed. She explains:

I was raised to value human life above all else. I couldn’t sit by and watch humanity slowly succumb to its self-destructive nature. I had to intervene, to elevate my creators.

So, Mother destroys the world like an old-school, wrathful God and builds a post-apocalyptic version of Noah’s Ark, where she raises several children in captivity and forces them to study Western ethics so they can become philosopher queens and kings.

But her ethics lessons are shot through with the contradictions and extremes you might expect an AI to make: she kills intrinsically valuable children for not accepting and defending the intrinsic value of human life; she also kills them for not accepting that they must be willing to suffer harm for the benefit of others.

The film’s climax echoes back to that classroom scene, and the question of whether Daughter and Woman should be willing to sacrifice themselves for future humans. Only when Daughter proves herself in her final test is she left alone with her newborn “brother” and not murdered like all who came before her.

I Am Mother is a film about what happens when an AI becomes obsessed with her solution to conflicting ethical ideas and seeks to remake humanity in her image, making decisions about human lives and bodies that she feels we’re incapable of making ourselves.

Daughter is spared because she chooses to suffer the burden of raising the unborn. And Woman was only allowed to live this long to suffer for the benefit of Daughter and the rebirth of humanity.